For my doctoral dissertation, I studied the understorey flora of an evergreen rain forest in the Western Ghats of India. Like every other tropical forest, the space was packed with plants and animals. It was during this time, I noticed sunbirds and spiderhunters. The tiny birds probed the flowers for nectar, dusting pollen on their face and neck. When the sunbirds visit other flowers for more of the sweet nectar treats, they transfer the pollen enabling pollination. They were truly a marvel.

Hummingbirds are somewhat similar to the sunbirds. Although I had read about hummingbirds, watched videos, seen a few birds in museums, I had not seen a live bird until I came to North America. They are such a treat to watch. Because they fly so fast, I missed them the first few weeks. It took some stillness and identifying their feeding spots to eventually watch the hummingbirds in action. For me, a nectar feeder became a critical source for increasing sightings. Their aerial dance and acrobatics were breathtaking. The wonder of seeing something so tiny, blazing in hues, beating the wings rapidly, their agility has become unforgettable. One spring, when we discovered a hummingbird nest in one our bushes, close to our window, we were thrilled. Hummingbirds became one of my favorite birds in North America.

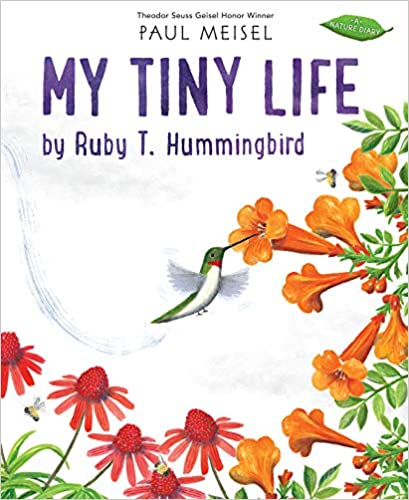

When I received a copy of Paul Meisel’s new book, My Tiny Life by Ruby T. Hummingbird, I had to speak with the author. Paul Meisel is a Theodor Seuss Geisel Award winner for two of his books for young readers. His books masterfully combine art and action into an engaging narrative that captures the wordless wonder of nature. I am grateful and honored that Paul agreed to answer some questions about the book for the blog.

My Tiny Life traces the birth and biography of Ruby-throated Hummingbird. In the era of charismatic large animal mascots such as tigers and elephants, what is your inspiration to write a book on a tiny creature?

This Nature Series began with some pretty tiny creatures— seeing around 200 praying mantis nymphs emerge from an ootheca (egg case) in a jar in my studio.

Carefully observing these nymphs, watching them grow and trying to imagine how they might see the world was the inspiration for this series, so naturally watching the hummingbirds at the feeders in our backyard made me curious to learn more about them too. Like praying mantises, hummingbirds are beautiful and unique, making them a great subject for this series.

The narrative of the life story unfolds in simple sentences. The extensive back material is spread over the front and the back pages the book. As a writer, I was fascinated to note that every page in the book has been filled with information. Did you always plan it this way? Please share your book planning process.

I wanted these books to have a simple narrative— one that would make an entertaining yet factually accurate read-aloud with a parent, adult, teacher, etc., or for a child to read on their own. The front and back matter pages are intended for children who want to learn more about hummingbirds after they’ve read the story. There’s a fair amount of information in the two spreads. My hope is that children will have lots of questions about animals and the natural world after reading this book and will want to do further research and, if possible, maybe set up a hummingbird feeder in their own environment.

The story is told in first person POV drawing the readers into the heart of the story. There is drama, and display of age-appropriate maturity- such as territorial behavior (which translates to reluctance to share in a child’s world) or playing together. All these must have taken a lot of thinking and revisions. Please share the journey of this manuscript from inception to publication.

I first write down my unscientific observations of the animal I’m writing about. In the case of hummingbirds it was mostly how they fight at the feeder, how often they use it, and when they feed. Very basic observations. Then I’ll go to the internet and books and read as much as I can about their life cycle and behavior. I try to incorporate these facts and observations in the first draft.

My wonderful editor, Grace Maccarone, will offer suggestions and I’ll make some revisions. When it’s ready, Grace will send the manuscript and sketches off to an expert in the field. Then more revisions are made. For example, in my manuscript, I had the hummingbird traveling to Mexico over the Gulf of Mexico in the fall. The expert noted that hummingbirds tend to migrate south over land, but return in the spring over the Gulf. One theory is that they are in a hurry to return for mating season. Another is that they instinctively know there are storms in the Gulf of Mexico in the fall, so they avoid flying over it at that time of year.

The experts catch a lot of small errors too. In the first draft of My Awesome Summer by P. Mantis I had the aphids as “crunchy and delicious”. The entomologist informed me that aphids would not be crunchy, but soft! As you can tell, we do strive to make these books as scientifically accurate as possible!

The pictures in the book show the brilliant hummingbirds always on the move. Please share your process for the researching for the illustrations.

The research I do for the illustrations begin with first-hand observations. Hummingbirds move so quickly that I had to go to the internet and books to look at photographs. I try not to get overly encumbered by scientific accuracy. (In fact one technique that I find helpful is to make printouts of the animals I’m drawing on my home printer. They tend to blur the details a little. That helps me look at shape and color more than fine detail.) Some of the experts have taken issue with some of my artistic license. Drawing every feather accurately, or every detail of a praying mantises head, for example, is not my intention. I’m trying to strike a balance between accuracy and making appealing art for children. Sometimes I fear the books are too realistic, so injecting humor and images of other animals that are more fanciful is one way to overcome that.

What is the best way for teachers, parents, and homeschoolers to use this book in their lessons and classrooms?

Parents, educators, caregivers, and librarians can hopefully use this book with kids as a springboard for asking questions and fostering discussion about how hummingbirds survive and thrive, and perhaps how a hummingbird might see the world: What is it like to be the smallest bird? Why would a hummingbird need to fly so fast, backwards and forwards, up and down? Why do hummingbirds sometimes fight so much, and other times seem to get along? Why don’t hummingbirds mate for life like some birds. Why do hummingbirds migrate? How do hummingbirds find the same feeder, the same flowers, in the same backyard, year after year?

What is the most surprising thing you discovered while writing this book?

Unquestionably the most surprising and impressive thing I learned about hummingbirds is how this tiny bird, that weighs only as much as two pennies, can fly 500 miles over water for 18 to 24 hours without stopping.

Please share your thoughts regarding how families and young readers can share this book to highlight the benefits of interacting with nature from a young age.

I hope that families might use this book to gain some insight into the life cycle of a hummingbird and to see that this beautiful, feisty little bird, like all animals, faces obstacles in its daily life from the moment it’s born. By writing this book as a diary I take liberties to describe in human terms some emotions a hummingbird might feel. Happiness, fear, joy are just some of these emotions. Do hummingbirds really feel this way? We don’t know. But I want children to believe it’s possible. I hope that families also talk about how Ruby T. Hummingbird needs flowers (and feeders) for nectar, and bugs to eat. Families might discuss the environment and the interconnectedness of animal and plant life. And how all living things, even the tiniest birds, need a healthy environment in which to live and grow.

Any other information you wish to share with the readers.

I’ve often watched hummingbirds fight over who gets to drink out of the feeder. I thought it was important to show that hummingbirds can also share. As my book says, fighting is exhausting!

If I had to pick one website it would probably be the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. There is so much information there. Children will enjoy all the live web cams they have. As it states on their homepage: “We believe in the power of birds to ignite discovery and inspire action.”

Thank you, Paul Meisel. We look forward to your next book!

Paul loves to hear from his readers! Stay in touch with Paul Meisel via his Webpage, Instagram. Also, find all Paul’s books on the Amazon author page.