We hand our children the most powerful attention-capture technology ever engineered by humanity — and then wonder why they can’t focus in a classroom. What’s happening inside their brains isn’t laziness. It’s a neurological emergency unfolding in slow motion.

The Numbers That Should Keep You Up at Night

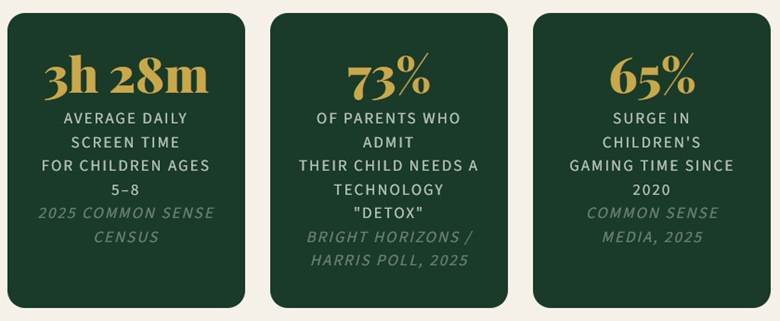

Let me be direct with you. The data coming out of 2025 is not encouraging — and most parenting headlines are burying the lead.

According to the 2025 Common Sense Media Census, children ages 5 to 8 now average 3 hours and 28 minutes of daily screen time. That’s the median. The distribution tail is terrifying: a significant portion of that cohort is clocking well over 4 hours — and some, closer to 6. Meanwhile, a 2025 survey by Lurie Children’s Hospital found that while parents believe 9 hours per week is a healthy target, their children are actually accumulating 21 hours — more than double the amount they themselves deem acceptable.

The gap between intention and reality is staggering. A 2025 Harris Poll commissioned by Bright Horizons found that 73% of parents openly admit their children need a “detox” from technology — including 68% of parents with children under six. Sixty percent reported their kids were using screens before they could even read.

But here is the part that demands your full attention. These are not passive activities. Short-form video platforms like YouTube Shorts, Ticktock, and Instagram Reels are specifically engineered to trigger rapid dopaminergic reward cycles. Every swipe delivers a micro-hit of novelty. Every auto play eliminates the cognitive friction that would otherwise give a developing brain a chance to disengage. The child is not simply “watching.” They are being neurologically trained — rewired, stimulus by stimulus — to expect a level of environmental input that no classroom, no dinner table, and no park can match.

Directed Attention vs. Soft Fascination: The Battle Happening Inside Your Child’s Brain

To understand what excessive screen time is doing to a young child’s developing brain, you need to understand two fundamentally different modes of attention — and why one of them is quietly destroying the other.

The Prefrontal Cortex: Command Center Under Construction

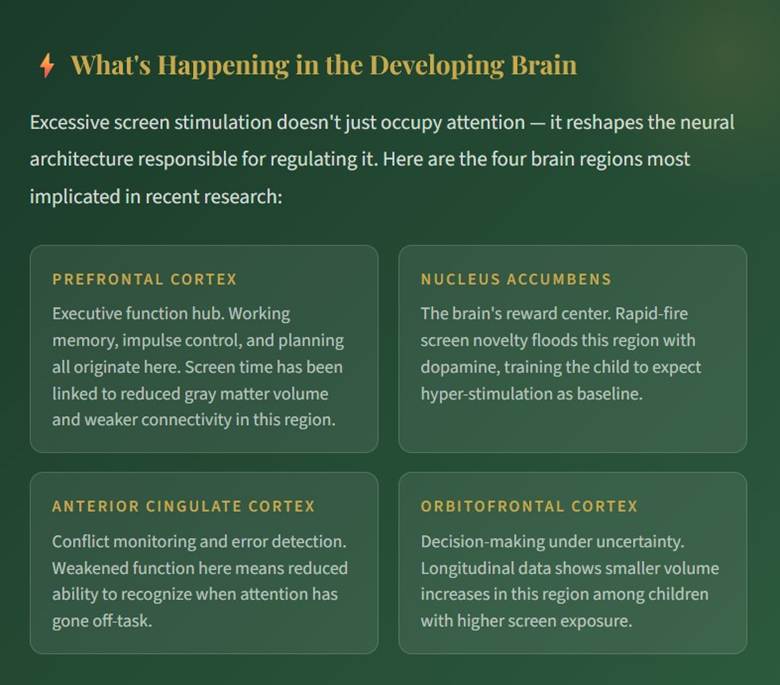

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is the last region of the brain to fully mature — a process that extends well into the mid-twenties. In a 6-year-old, it is in one of its most critical windows of structural development. This is the region responsible for executive function: working memory, impulse control, planning, and the ability to delay gratification. It is, in neuroscientific terms, the architecture of self-regulation.

A landmark 2023 meta-analysis published in Taylor & Francis, led by Chair Professor Hui Li of The Education University of Hong Kong, synthesized neuroimaging data and concluded that screen time leads to measurable changes in the prefrontal cortex — the very region governing working memory and flexible thinking. In December 2025, a longitudinal study following children for over a decade found that high screen exposure before age two was linked to premature specialization in brain networks involved in cognitive control — changes that later translated to slower decision-making and increased anxiety by adolescence.

In October 2025, a study published in Translational Psychiatry (Shou, Yamashita & Mizuno, 2025) used neuroimaging data to demonstrate that screen time weakened fronto-striatal connectivity — the neural pathway linking the prefrontal cortex to the brain’s reward circuitry. In plain terms: the more screen time, the weaker a child’s ability to govern their own impulses.

The Two Modes of Attention

In 1995, psychologists Stephen and Rachel Kaplan introduced Attention Restoration Theory (ART) — a framework that has since become one of the most empirically supported models in environmental psychology. Their core insight was elegant: human attention operates in two fundamentally different modes, and confusing the two is the root cause of modern cognitive exhaustion.

Directed Attention is effortful, voluntary, and finite. It’s what your child uses when watching a fast-paced YouTube video — constantly tracking visual change, suppressing irrelevant stimuli, and processing novel information at machine-pace. It depletes. Rapidly.

Soft Fascination is effortless, involuntary, and restorative. It’s the mode activated when watching clouds drift, listening to birdsong, or observing water ripple across a pond. As a 2024 review in the Journal of Imaging confirmed, soft fascination does not require cognitive effort — it simply holds attention gently, allowing the directed attention system to recover.

| Measure | Screen Time (Directed Attention) | Nature Exposure (Soft Fascination) |

| Attention Mode | Forced / Effortful | Effortless / Involuntary |

| Heart Rate Response | ↑ Elevated (sympathetic activation) | ↓ Lowered (parasympathetic dominance) |

| Cortisol Levels | ↑ Dysregulated; impaired diurnal rhythm | ↓ Reduced by up to 15% in green settings |

| Dopamine Pattern | Spike-and-crash (reward-seeking loop) | Stable; no artificial reward trigger |

| Prefrontal cortex Recovery | None — further depletes directed attention | Active restoration of executive function |

| Effect on Attention (post-exposure) | Reduced focus; increased impulsivity | Improved concentration; calmer behavior |

Sources: Kaplan & Kaplan (1995), Attention Restoration Theory; Faber Taylor & Kuo (2004), University of Illinois; U.S. National Park Service, Nature Benefits Research Summary; Shou et al. (2025), Translational Psychiatry; European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2024).

The physiological contrast is stark. Research documented in Psychology Today has confirmed that screen-based activities function as valid physiological stressors — triggering changes in autonomic tone, heart rate, blood pressure, and cortisol output comparable to acute psychological stress events. Meanwhile, the U.S. National Park Service’s synthesis of nature-health research reports that physical activity in green settings lowers cortisol by approximately 15%, and that just 20 minutes of walking in a park improves concentration and school participation.

Nature Is Not a Hobby. It Is the Antidote.

For years, we have treated time in nature as optional — a weekend luxury, a summer camp enrichment activity, something to squeeze in between the “real” obligations of modern childhood. This framing is not just incomplete. It is dangerous.

The evidence is no longer suggestive. It is directive. Dr. Andrea Faber Taylor, a specialist in human-environment dimensions at the University of Illinois, found in a controlled field experiment that a single 20-minute walk through a park produced concentration improvements in children with ADHD that were comparable in effect size to methylphenidate — the most commonly prescribed stimulant medication for the condition. Twenty minutes. A park. No prescription required.

A longitudinal study published in The Lancet Planetary Health tracked nearly 50,000 children born in New Zealand and found that consistent exposure to green space during childhood reduced the risk of developing ADHD by up to 33%. This is not a marginal effect. This is a population-level finding.

And the mechanism is well understood. A 2025 study on cognitive fatigue recovery confirmed that nature draws attention “gently” — without the resistance or inhibition required in urban or screen-based environments. Unlike screens, which demand and deplete directed attention, nature allows the brain to shift into a state of effortless engagement. The directed attention system rests. The prefrontal cortex begins to recover.

What Happens When Families Actually Unplug

📰 Fortune Well · March 2025

The Detox Paradox: Parents Know, But Don’t Act

Fortune Well reported in March 2025 on the alarming gap between parental awareness and action. Rachel Robertson, Bright Horizons’ chief academic officer, described how using screens as a default calm-down tool — in grocery stores, in cars, at restaurants — quietly erodes a child’s ability to self-regulate. “They have missed an opportunity to develop regulation skills, to manage emotions,” she explained. The article highlighted that while 49% of parents are concerned about their children’s mental health, 55% still use screens as a bargaining chip for compliance — a pattern that compounds daily.

📺 KWTX News · October 2025

A Texas Family’s Monthly Reset

KWTX reported in October 2025 on the Koerth family in Valley Mills, Texas, who began conducting monthly weekend-long digital detoxes. The family spends time exploring the creek near their home, looking for arrowheads and observing wildlife. Mother Tabetha Koerth, a digital marketer who understands the psychology of online engagement firsthand, described how the practice shifted the family dynamic — creating space for the kind of unstructured, nature-based play that child development researchers identify as critical for cognitive recovery.

🏥 URMC / University of Rochester · 2025

Neurologists Sound the Alarm

The University of Rochester Medical Center published a 2025 explainer in which pediatric neurologist Dr. Justin Rosati stated plainly that studies have shown abnormalities in prefrontal cortex activation patterns among children with high screen exposure. The piece emphasized that while the science is still evolving regarding long-term structural changes, the functional impact on attention and behavior is already measurable — and that parents should treat screen boundaries as a developmental priority, not an optional preference.

Nature-Based Activities for the Whole Family

You don’t need a national park or a countryside retreat. You need 20 minutes and a patch of green. Here are activities designed around the principles of Attention Restoration Theory — each one engineered to activate soft fascination and give your child’s prefrontal cortex the recovery it needs.

The Water Watch

Sit near any moving water — a creek, fountain, or even a garden hose flowing into a bucket. Watch it. Say nothing. Let the rhythmic movement do the work.

All Ages

🐜 The Ant Trail

Find an ant colony — in sidewalk cracks, near a tree, in soil. Observe for 10 minutes. Track where they go. No intervention. Just watching nature solve problems.

Ages 4–10

☁️ Cloud Stories

Lie on your back in any outdoor space. Watch clouds for 15 minutes. No phones, no prompts. Let the imagination wander — the original “streaming” service.

Ages 3+

🍂 The Sensory Walk

Walk barefoot on grass or soil for 20 minutes. Feel the temperature change, the texture. Listen to what’s around you. Name five things you can smell. This is full-spectrum sensory restoration.

Ages 5+

🌱 Dirt & Seeds

Plant something — anything. A seed, a bulb, a cutting. Dig with hands, not tools. The tactile engagement and the delayed reward of growth mirror exactly what the prefrontal cortex needs to practice.

Ages 4+

🦋 The Silent Safari

Walk through any green space — backyard, park, trail — in complete silence for 10 minutes. Then take turns sharing what you noticed. Teaches observation without the pressure of performance.

Ages 6+

The research is unambiguous: even short, repeated exposures to nature produce measurable cognitive benefits. A 2025 study on fascination and nature confirmed that participants made fewer, longer visual fixations on natural scenes — a signature of effortless, restorative attention processing. You don’t need to overhaul your life. You need to make nature non-negotiable.

The screen isn’t the enemy. But in its current, unchecked form — in the hands of a 6-year-old whose prefrontal cortex is still under construction — it is competing with the single most powerful neurological recovery tool available to us: the natural world. The question is not whether your child needs more nature. The question is how long you’ll wait before making it a priority.

Start Your Detox Today

Sources & Further Reading

- Mann, S., Calvin, A., Lenhart, A., & Robb, M.B. (2025). The Common Sense Census: Media Use by Kids Zero to Eight. Common Sense Media. commonsensemedia.org

- Bright Horizons / Harris Poll (2025). Modern Family Index. brighthorizons.com

- Lurie Children’s Hospital (2025). Screen Time Statistics Shaping Parenting in 2025. luriechildrens.org

- Li, H. et al. (2023). Children’s brains shaped by their time on tech devices. Taylor & Francis / ScienceDaily. sciencedaily.com

- Neuroscience News (Dec. 2025). Early Screen Time Linked to Long-Term Brain Changes, Teen Anxiety. neurosciencenews.com

- Shou, Q., Yamashita, M. & Mizuno, Y. (2025). Association of screen time with ADHD symptoms: the mediating role of brain structure. Translational Psychiatry, 15, 447. nature.com

- Rosati, J. (2025). Screen Time and the Developing Brain. UR Medicine. urmc.rochester.edu

- Kaplan, S. & Kaplan, R. (1995). Attention Restoration Theory. See: PMC review, 2024

- Faber Taylor, A. & Kuo, F.E. (2004). A Potential Natural Treatment for ADHD. American Journal of Public Health, 94(9). ajph.aphapublications.org

- Donovan, T. et al. (2019). Association between exposure to the natural environment and ADHD in children in New Zealand. The Lancet Planetary Health. thelancet.com

- U.S. National Park Service. Nature Makes You… nps.gov

- Greenfield, B. (2025). 68% of parents say kids need a ‘detox’ from technology. Fortune Well. fortune.com

- KWTX (Oct. 2025). Family digital detox helps reconnect parents and children. kwtx.com